UPDATE 24 October 2014

The Affinity team is confirmed as preferred bidder in the race to replace the fixed wing training fleet. Final negotiations underway, FlightGlobal reports ("T-6C to head UK military training renewal", by Craig Hoyle, 24 october 2014). It is also confirmed that Linton on Ouse will no longer be a training centre, with the Tucano replacement based in RAF Valley. There is no official word on the base closing, yet, but it looks like it is the natural follow on event.

Meanwhile, as the article says, 57(R) Squadron has moved into RAF Cranwell by 6 October 2014.

Royal Air Force Number

22 (Training) Group is responsible for the recruitment, selection, initial and professional

training of RAF personnel as well as providing technical training for the Army

and Royal Navy. The Group provides education and continual development

throughout individuals’ RAF careers. The HQ is based in High Wycombe.

22 Group does not deliver just Flying Training. It also controls Signals training, including the Royal School of Signals, and other technical training, but the purpose of this article is to overview the air training, which is delivered under Director Flying Training (DFT).

DFT directly controls the Central Flying School in RAF Cranwell, the 1 Flying Training School in RAF Linton-on-Ouse, the Defence Helicopter Flying School DHFS RAF Shawbury, the 3 Flying Training School in Cranwell and the 4 Flying Training School in RAF Vallery.

No 2 Flying Training School has been stood up this year to control Air Cadet flying training, as will be seen later in the article, but the organisation has no direct link to the frontline crew formations.

Elementary Flying Training is delivered by No 1 Elementary Flying Training School, with HQ in Cranwell.

As of early 2014, an estimate of 250 ab initio pilots and 60 ab initio crewmen enter the system each year. The british flying training pipeline also trains some 40 foreign students on average, under International Defence Training agreements and contracts, such as with Saudi Arabia.

The UK Military Flying Training System contract

In 2008, the MOD signed a 25-year Public Private Partnership

contract for the delivery of flying training to students from all three the

armed services. The contract was signed with ASCENT, a joint venture between

Lockheed Martin and Babcock. The role of Babcock is aircraft and equipment

maintenance, and airfield support. Lockheed Martin and CAE personnel are

involved for support to simulators and electronic training.

As part of the agreement, the MOD

sets the requirements and standards of training, while supplying airfields and

fuel. ASCENT is responsible for delivering the training courses and for

renewing the training aircraft fleets. ASCENT has first of all taken over the

legacy, existing fleets and training arrangements, and started to deliver the

reworked capability areas in progression.

The first capability area to be

touched was Fast Jet Training (FJT), with the order of the 28 Hawk T2 advanced

jet trainers and the construction of a new hangar and a two-storey training

centre in RAF Valley. The first course began on 2 April 2012.

The second capability area to be

touched was Royal Navy Observer training, with ASCENT signing to take over the

Observer Training Flight in 703 NAS at Barkston Heath, and with an order placed

for four new Beechcraft King Air 350 (Avenger T1 in Royal Navy service) trainer

aircraft, assigned to 750 NAS in Culdrose. Avenger flying operations began on

11 April 2012, with the first four Observers graduated in January 2013.

The renewal of other capability

areas has been slowed down by reviews, budget uncertainty and cutbacks to the

number of crews the UK need to train as the armed forces shrink. The cuts of

2010, in particular, were devastating in this sense, and led to the disbandment

of several legacy training squadrons.

ASCENT is still due to renew

Elementary Flying Training (EFT), Basic Flying Training (BFT), Multi Engine

Pilot Training (MEPT), Rotary Wing Training (RWT) and the RAF Rear Crew

Training (RCT2, with RCT1 being the RN Observers training, delivered).

In 2012, with the turmoil of cuts

and disbandments passed, it was decided that ASCENT would proceed with the

renewal of EFT, BFT and MEPT. A Request For Proposals was put out in December,

and three team bidders stepped forth:

BAE Systems, in team with Babcock, Gama

and Pilatus proposed maintaining the existing Grob 115E (Tutor T1) fleet for

the EFT, while using Pilatus PC-21s

as replacement for Tucano T1 for BFT and new Cessna

Citation Mustangs replacing the Beechcraft King Air 200 for the MEPT.

An EADS Cassidian-led team comprising CAE and Cobham proposed the Grob G120TP

for EFT and the Beechcraft T-6C for BFT. Their proposal

for MEPT is not known.

Finally, Affinity Group, a team made up by Elbit Systems and KBR,

proposes the Grob G120TP for EFT, the Beechcraft T-6C for BFT and the Embraer

Phenom 100 for MEPT. Note that both of the known proposals for MEPT come with

twin turbofans, instead of the turboprops which have been the norm this far.

The RAF going ahead will only have the A400M and Shadow R1 propelled by

multiple turboprops, and evidently it is assessed that turbofans will deliver

better training. It still is curious, however, that the Beechcraft King Air 350

is not considered: one would think that commonality with the Shadow R1 fleet

and Avenger fleet would still be attractive, even if maintenance is carried out

by Babcock under the contract arrangements.

News reports suggest that the Affinity Group is going to win. An

announcement is (or at least was) expected before the end of this year. At ILA Berlin

Air Show earlier this year, a presentation by Ascent said that contract award

is expected in the first quarter of 2015. In May 2017 Cranwell would begin

receiving the first new Elementary Flying Training aircraft, and the first

student course would start in December 2017.

The new Basic Fast Jet Trainers would begin arriving at RAF Valley in

April 2018, with the first student course in January 2019. The METP would see deliveries

of the new trainer aircraft beginning at Cranwell in October 2017, with the

first student course starting in June 2018.

|

| The Phenom 100 could be the next multi engine trainer |

The Rotary Wing Training should select the way ahead by around 2018. The

replacement of the legacy training fleet was delayed in 2012, and the contract

covering the existing fleet and arrangements was extended out to 2018, but the

old Squirrel and Griffin are increasingly inadequate, with their old avionics

being in no way representative of the glass cockpits and systems the crews will

find on passage to the frontline. The Rotary Wing Training at DHFS Shawbury currently

is delivered

by FB Heliservices.

AINoline in one

article said that a RFP for the

renewal of the Rotary Fleet was expected this month, but so far there have been

no news. Confirmations that the competition is to begin soon have filtered,

though, and Airbus is already positioning itself to offer the EC-130 and

EC-135, Flightglobal

reported from Farnborough.

Work has also begun to define the RCT2 training package for rear

crewmen.

By 2019, if there aren’t further changes and delays, all the training

packages might be delivering. One current training base, RAF Linton-on-Ouse, is

expected to lose its Basic Fast Jet Training role, which will be consolidated

in RAF Valley under current plans.

As is explained in greater detail in this article, RAF Valley is very

likely to see the disbandment of 208(R) Squadron by around 2016, and it appears

that the idea is to use the room freed by it to house the BFT school and its

single flying squadron.

Another installation which is seen as at risk is Middle Wallop. The Army

is resisting calls to concentrate helicopter training completely in Shawbury,

as it believes that Middle Wallop is perfectly located to provide the right

challenges to pilots undergoing Operational Training Phase: the base’s airspace

is crowded, and the closeness to Salisbury Plain and to important Joint

Helicopter Command bases and fleets is assessed as being extremely beneficial

to training.

670 AAC Squadron, in Middle Wallop, uses 9 Squirrels updated by the army

with a moving map display, a simulated defensive aids system panel and night

vision goggle-compatible anti-collision lighting to support formation flying at

night. They are able to deliver a much more complete and operationally relevant

preparation to crews before they move on to 671 Sqn (OCU, or better Conversion

To Type unit for Lynx, Gazelle and Bell 212) or 673 Sqn (Conversion to Type

unit for Apache).

The future of Middle Wallop hangs in the balance of a number of choices

regarding the delivery of training in the future. Will the Army’s Operational

Training Phase be sacrificed on the altar of savings, or anyway absorbed

somewhat by the future RWT in Shawbury? As the Wildcat replaces the Lynx, the

Gazelle eventually leaves service and the handful of Bell 212 face an uncertain

future, will 671 remain? The Wildcat fleet has its training centre in

Yeovilton, and 652 Sqn is earmarked as the OCU: either 671 Sqn vanishes and

gives its role completely to 652, or both squadrons stay, one delivering

Conversion to Type training and one Conversion to Role (more advanced training,

specifically focused on operational, tactical use of the machine). The same

uncertain future faces 673 and the Apache force. As the attack

regiments restructure, it is not at this

stage publicly known how training will be reorganized.

The Apache pilots, after completing their initial training or after

coming from another type, move to 673 Sqn in Middle Wallop. This is the Apache

Conversion To Type training squadron, which delivers 8-months training courses

to form the crews of the attack helicopter.

Achieving conversion to type, however, is not at all the end of the training. Conversion to Role prepares the crews for actually flying combat missions.

Achieving conversion to type, however, is not at all the end of the training. Conversion to Role prepares the crews for actually flying combat missions.

3 and 4 Regiment AAC have borne the burden of a constant presence in

Afghanistan for all these years, by adopting a two-year cycle that sees one

Regiment committed to operations and one in supporting role.

For example, in its operational year, 4 Regiment would cover the 12 months by deploying each of its three squadrons for a 4-month tour, modelled on RAF guidelines (which have been selected by Joint Helicopter Command, the higher authority the AAC responds to).

In the same 12-months period, 3 Regiment, in the supporting role, would deliver Mission Rehersal Exercise (MRX) support to troops preparing for deployment; Operational Conversion Training and a token Contingency force available for new operations, such as Op Ellamy in 2011.

One squadron on rotation between the three in the Supporting regiment would be tasked as Conversion To Role (CTR) unit, inglobating the Air Manoeuvre Training and Advisory Team (AMTAT). The Squadron would also hold Station Airfield responsibilities, looking over Wattisham, and would deliver training for shipboard operations, delivering Deck Landing Qualifications (DLQ).

Effectively, this arrangement was considered a 5 + 1 solution of five deployable squadrons and one training unit.

For example, in its operational year, 4 Regiment would cover the 12 months by deploying each of its three squadrons for a 4-month tour, modelled on RAF guidelines (which have been selected by Joint Helicopter Command, the higher authority the AAC responds to).

In the same 12-months period, 3 Regiment, in the supporting role, would deliver Mission Rehersal Exercise (MRX) support to troops preparing for deployment; Operational Conversion Training and a token Contingency force available for new operations, such as Op Ellamy in 2011.

One squadron on rotation between the three in the Supporting regiment would be tasked as Conversion To Role (CTR) unit, inglobating the Air Manoeuvre Training and Advisory Team (AMTAT). The Squadron would also hold Station Airfield responsibilities, looking over Wattisham, and would deliver training for shipboard operations, delivering Deck Landing Qualifications (DLQ).

Effectively, this arrangement was considered a 5 + 1 solution of five deployable squadrons and one training unit.

Under Army 2020, if the plan hasn't been revised further, the idea seems

to be to reduce the Attack Regiments to binary formation, with two squadrons

each, in line with the new binary structure of 16 Air Assault Brigade.

In addition, one squadron, while no longer frontline tasked, would remain as “OCU” unit: this could be, judging from the fate of 654 Sqn, the future of whatever squadron will be selected within 3 Regiment AAC once involvment in Herrick is over and the regiment is restructured to its binary Army 2020 structure.

In addition, one squadron, while no longer frontline tasked, would remain as “OCU” unit: this could be, judging from the fate of 654 Sqn, the future of whatever squadron will be selected within 3 Regiment AAC once involvment in Herrick is over and the regiment is restructured to its binary Army 2020 structure.

What is not clear is if this “OCU” based in Wattisham would complement

673 Sqn by delivering Conversion to Role training, or if it would replace 673

and deliver both Conversion to Type and Conversion to Role courses.

The future of 671 and 673, their continued existence and their basing,

will be decisive for the future of Middle Wallop. It is far from impossible to

imagine the MOD pressing the Army to concentrate Wildcat CTT and CTR in

Yeovilton and concentrate Apache training in Wattisham, in order to close down

Middle Wallop.

The future of 670 Sqn and Operational Training Phase is also crucial for

the future of the base. Its replacement might come through a new requirement,

outside UK MFTS, which was explained by deputy commander of Joint Helicopter

Command, Brigadier Neil Sexton, in January 2014. The brigadier went on record

saying that the MOD is now looking at a Surrogate Training requirement, which might help cover the Operational Training requirement and

download some of the training flying from expensive Wildcat and Apache

airframes to a much cheaper, but representative, machine.

In January, the idea was described as having small fleet of smaller, cheaper surrogate training helicopters (indicatively six for each base) equipped with dummy systems and adequate human-machine interface to enable highly realistic training at lower cost. The pilots will need to be able to move seamlessly from the surrogate to the real thing.

A key factor is that this requirement would be detached from the DHFS, which would continue to deliver Initial Training.

In January, the idea was described as having small fleet of smaller, cheaper surrogate training helicopters (indicatively six for each base) equipped with dummy systems and adequate human-machine interface to enable highly realistic training at lower cost. The pilots will need to be able to move seamlessly from the surrogate to the real thing.

A key factor is that this requirement would be detached from the DHFS, which would continue to deliver Initial Training.

Such Surrogate Trainers could be an excellent solution, but being based

alongside the helicopters they would represent, they would do nothing to save

Middle Wallop, as they would be housed instead in Yeovilton, Wattisham, Odiham,

Benson.

In other words, going ahead, as the training pipeline is renewed, at

least two bases risk being lost: RAF Linton-on-Ouse and Middle Wallop.

The UK MFTS, on its part, will go ahead with just four bases: Barkston

Heath with the Defence Elementary Flying School; Shawbury with the Defence

Helicopter Flying School, Cranwell and Valley, plus Culdrose if we include 750

NAS and its operations.

Another training unit that will be impacted in future is the SARTU, based in RAF Valley. The Search and Rescue Training Unit will undoubtedly be affected by the passage of SAR duties from the military to the Depertment of Transport in 2016.

SARTU provides ab initio rearcrew students with an introduction to SAR

helicopter techniques in both the Winch Operator and Winchman roles.

This training includes mountain and overwater helicopter operations.

SARTU also provides a selection course and dedicated rearcrew training

to meet the needs of the UK SARF and 84 Sqn RAF. 84 Sqn, based in Cyprus, will remain and will maintain its SAR capability, so a residual SAR training capability will be needed, but it is not clear how it will be delivered.

On behalf of DHFS, SARTU also delivers tailored SAR courses to foreign and commonwealth military and civilian customers.

Finally, the unit runs a number of staff courses to form Qualified Helicopter Instructors (QHI) and Qualified Helicopter Crewman Instructors.

The training pipeline

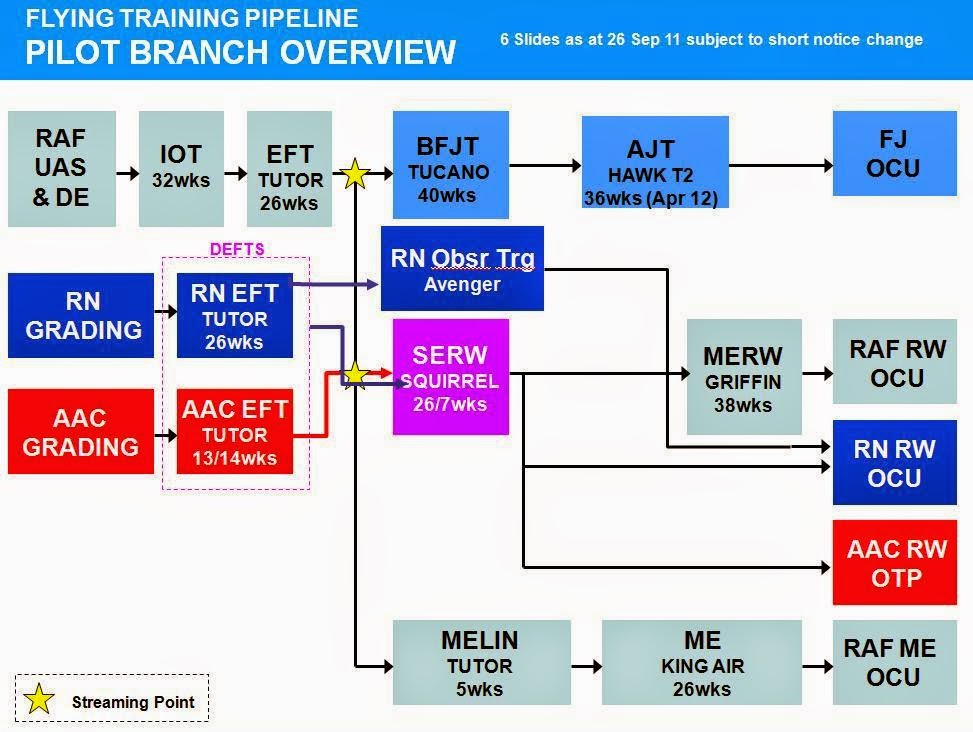

A 22 Group presentation, released in 2011, shows the arrangement of

flying training post-SDSR. I’ve modified the slides slightly, to include the RN

Observer course and to include training squadron indications.

In more detail, here I will explain

the passages of the training process:

RAF Direct Entry personnel and/or

trainees with University Air Squadron experience first of all undergo the

Initial Officer Training IOT at the Officer and Aircrew Training Unit (OACTU),

RAF College Cranwell. They then move into the flying training pipeline,

beginning with ground school courses in Cranwell (No 3 Flying School) which are

the same for all three services, and thus Joint in nature (purple color in the

graphic).

RAF students then progress into RAF No

1 Elementary Flying Training School, which puts them into courses flying the

Grob Tutor. As of 2011, the course lasts 24 weeks, including 55 flying hours.

The school stood up in 2005 with 3

squadrons: 16 (R) Sqn at Cranwell, 57 (R) Sqn at Wyton and 85 (R) Sqn at Church

Fenton.

85(R) Squadron was disbanded in

August 2011 due to the reductions coming from the SDSR 2010 and RAF Church

Fenton was closed down during 2013.

57(R) Squadron is due to transfer

into Cranwell by the end of August as Wyton ceases to be a flying station and

fully transforms into the Joint Forges Intelligence Group station, part of

Joint Forces Command.

|

| Tutor T1 |

Following the EFT phase, RAF students

are streamed either to the multi-engine (ME) line or to the fast jet (FJ) line

or the rotary wing line.

Army Air Corps and Royal Navy

personnel are first graded by the squadrons 676 AAC in Middle Wallop and by 727

NAS in Yeovilton respectively. Both squadrons use a handful of Grob Tutor

aircraft supplied by Babcock under contract for this task.

After moving through ground school

in Cranwell, Army and RN students move to the Defence Elementary Flying

Training School in Barkston Heath, where they train on the Tutor aircraft of

either 674 AAC or 703 NAS. The courses are a bit different: RN personnel flies

55 hours vs 40 for the Army, and has 24 weeks long courses compared to 13 to 14

weeks for the Army personnel.

A limited number of Army students

move into the Multi Engine stream to train for the Defender / Islander fleet of

5th Regiment AAC, while the others progress into the Rotary Wing

Stream.

RN students move on to the Rotary

Wing Stream or to the Fast Jet Stream.

In addition, the Royal Navy needs to

train Observers: they receive a

purposefully designed training from Observer Training Flight, 703 NAS, before

moving to 750 NAS for training on the Avenger T1 (Beechcraft King Air 350

supplied under UK Military Flying Training System).

In 750 NAS, RNAS Culdrose, the

observer students are prepared for systems and sensors management and all-weather

aircraft operations before going to serve into the rotary wing pipeline.

The Fast-Jet path moves on through

No 1 Flying Training School in RAF Linton-on-Ouse, where they fly on the Tucano

T1 with 72(R) Squadron. 124 flying hours are amassed as part of a 40 weeks

instruction course.

The other squadron of the school, 76

Sqn, was disbanded as a consequence of the SDSR 2010.

When Basic Fast Jet Training (BFJT)

is completed and the wings are obtained, the training moves to RAF Valley,

where No 4 Flying Training School completes the job delivering Advanced Jet

Training with the Hawk T2 of IV(R) Sqn, with a course of some 36 weeks

including 120 flying hours.

The ME path includes a 5 weeks

Multi-Engine Lead-In (MELIN) course flown on Tutor and overseen by 45(R)

Squadron, before the Multi-Engine training proper is carried out on Beechcraft

King Air 200 flying from Cranwell with 45(R) Squadron, followed by the passage

to the relevant Multi-Engine OCU squadron.

|

| Beech King Air 200 |

For ME training, RAF Students coming

from Elementary Flying Training and students from the Defence Helicopter Flying

School which decide to re-role have to pass through a Multi-Engine Lead In

(MELIN) course lasting 5 weeks with 12 flying hours on Grob Tutor.

This is not necessary for more

experienced personnel re-roling or re-streaming from other branches. Depending

on their preparation, they are sent either to Multi Engine Advanced Flying

Training – Long courses of Short courses, which lead eventually to passage in

the fleet OCU squadrons.

Army personnel directed to the

Defender/Islander fleet move through a purposely designed MELIN course lasting

6 weeks and including 19 flying hours on Tutor, before passing through a ME AFT

Long course.

RAF personnel moving to the rotary

stream (either coming out of RAF elementary flying training or re-streaming

from various points of the fixed wing careers / training paths) move through

the same ground courses faced by Army and Royal Navy pilots coming from the

Defence Elementary Flying Training School.

After the classroom instruction, all

students, from all three services, move through the Single Engine Rotary Wing

courses delivered by 660 Sqn AAC and 705 NAS at the Defence Helicopter Flying

School in RAF Shawbury. The helicopter employed is the Squirrel HT1.

After this course is completed,

paths separate: RAF personnel streams into the (60) Squadron Lead In Course

(SLIC), and moves on towards Multi Engine Advanced Rotary Wing training, flying

77 hours on the Griffin HT 1 of 60(R) Squadron RAF.

Army and Royal Navy personnel,

curiously, do not face a multi-engine training course, despite all the Army and

RN helicopters being multi-engine (with the exception of Gazelle, as long as it

is in service). Navy personnel instead move through the Maritime Ops Lead In

Course (MOLIC) at 705 NAS before reaching the OCU squadrons. They only receive

their wings after completing the training at the OCU squadrons.

Army personnel face the Army Lead In

Course (ALIC) at 660 Sqn AAC, before moving to Middle Wallop for the

Operational Training Phase (OTP) flown on the Squirrel HT2 of 670 Sqn AAC. The

successful students get their Wings, and then move on to 673 Sqn (Apache OCU)

or 671 Sqn (Lynx, Gazelle, Bell 212 OCU) for Conversion To Type training.

Crewmen (loadmasters, EW and intelligence operators etcetera) are trained

starting with the Non-Commissioned Aircrew Initial Training Course, lasting 11

weeks and delivered by the Officer and Aircrew Training Unit (OACTU) RAF

Cranwell, followed by a Weapon System Operator Generic (WSOp Generic) lasting

ten weeks and delivered by 45(R) Sqn.

Crewmen and Navigator / WSO for

Tornado were once trained on the Dominie T1 (version of the BAE HS.125) by

55(R) Squadron at Cranwell, but the squadron was disbanded and the aircraft

withdrawn from service in January 2011.

As of 2014, however, the way

forwards for rear crewman (Fixed Wing) training is still a bit up in the air.

The RAF is considering ways to incorporate some of its crewmen training needs

into 750 NAS at Culdrose, for example, while it waits for a more effective

solution that might be years away. The Military Flying Training System project

includes a RAF Rear Crew Training requirement (RCT2, since RCT1 has been

contracted, delivered and is operating, being 750 NAS itself) but so far it has

not progressed in any significant way. The purchase of a new fleet of rear crew

training aircraft is not currently funded, so it is to be assumed that the RAF

will have to make do for quite a while still, meeting the requirement by

exploiting the aircraft used by 45(R) Squadron for Multi Engine training, and

possibly exploiting some of the capability of the RN’s Avenger aircraft in 750

NAS.

The Flying Training Schools

No 3 Flying Training School – RAF Cranwell

Flying Wing provides training for

multi-engine pilots using the seven Beechcraft King Air B200 aircraft of No

45(R) Squadron.

The Wing also incorporates Central

Flying School (CFS) Tutor Squadron, Ground School Squadron, Air Traffic Control

Squadron, Operations Squadron, General Service Training Squadron and the

Meteorological Office.

The Central Flying School is the RAF’s primary institution for the

training of military flying instructors, for testing individual aircrew, audit

the Flying Training System, give advice on flying training and provide the RAF

Aerobatic Team. Established at Upavon on 12 May 1912, the Central Flying School

(CFS) is the longest serving flying school in the world.

No 1 Elementary Flying Training School – RAF Cranwell

(1 EFTS) has its Headquarters at

Rauceby Lane, Royal Air Force College Cranwell together with the Central Flying

School. The School is responsible for fixed wing elementary flying training for

pilots of all 3 UK armed forces and for pilots from some overseas countries.

Following the disbandment of 85(R) Squadron and the closure of RAF Church Fenton, the school comprises two RAF squadrons:

Following the disbandment of 85(R) Squadron and the closure of RAF Church Fenton, the school comprises two RAF squadrons:

16 (R) Sqn at Cranwell,

57 (R) Sqn at Wyton; transferring to Cranwell this year

57 (R) Sqn at Wyton; transferring to Cranwell this year

The EFTS stream also includes 703

Naval Air Squadron and 674 Squadron Army Air Corps at the Defence Elementary

Flying Training School, RAF Barkston Heath.

Flying the Tutor and “training the trainers” for the EFTS stream is 115 (R) Sqn of the Central Flying School (CFS) at Cranwell (transferring to RAF Wittering this year), and 14 University Air Squadrons (UASs) based at 12 different locations around the country.

Flying the Tutor and “training the trainers” for the EFTS stream is 115 (R) Sqn of the Central Flying School (CFS) at Cranwell (transferring to RAF Wittering this year), and 14 University Air Squadrons (UASs) based at 12 different locations around the country.

The University Air Squadrons offer

flying training to undergraduates and represent a way to experience life in the

RAF without / before joining. There is no obligation to sign up for RAF service

at the end of the UAS period. All UAS are equipped with the Tutor T1. As we

have seen earlier in the description of the training pipeline, the training in

the UAS is not necessarily part of the preparation of RAF crews.

- Bristol University Air Squadron Colerne airfield

- Cambridge University Air Squadron RAF Wittering

- East Midlands UAS RAF Cranwell (moving to Wittering in 2014)

- East of Scotland Universities Air Squadron RAF Leuchars

- Liverpool University Air Squadron RAF Woodvale

- Manchester and Salford Universities Air Squadron RAF Woodvale

- Northumbria University Air Squadron RAF Leeming

- Oxford University Air Squadron RAF Benson

- Southampton University Air Squadron Boscombe Down

- University of Birmingham Air Squadron DCAE Cosford

- Universities of Glasgow & Strathclyde Air Squadron Glasgow International Airport

- University of London Air Squadron RAF Wyton (moving to Wittering in 2014)

- Universities of Wales Air Squadron MOD St Athan

- Yorkshire Universities Air Squadron RAF Linton-on-Ouse (moved from RAF Church Fenton in 2013)

No 1 Flying Training School – RAF Linton-on-Ouse

The school delivers Basic Fast Jet

training, using the Tucano T1. The school used to have two BFJT squadrons,

72(R) and 207(R), plus 76(R) squadron to deliver air navigation training, as

part of the WSO courses.

However, the SDSR 2010 with its cuts

ended the WSO training line, leading to the disbandment of 76(R) Squadron in

May 2011. The reduction in the number of personnel to be trained also led to

the disbandment of 207(R) in January 2012.

The School retains a single flying squadron,

72(R).

Personnel from Central Flying School

is on the base to train the Tucano Qualified Flying Instructors.

No 2 Flying Training School – RAF Syerston

This school was stood up only

recently, and in January 2014 took command of the RAF Air Cadet’s national

gliding, which means controlling the world’s largest fleet of gliders. The

school commands 25 Voluntary Gliding Squadrons which deliver a training program

for up to 45.000 cadets in the age range 13 to 19. The school represents the

first full time reserve officer position, at Group Captain rank, in a flying

command appointment. Full time reservist officer Group Captain John Middleton

is the first commander of the school.

The school brings training for the

Air Cadet Organization back under RAF roof. The ACO is sponsored by the Royal

Air Force but is not a recruiting organization. It is to be noted, however,

that up to 50% of RAF personnel will on average have been a cadet in youth.

The ACO is made up by two areas:

The Air

Training Corps is the RAF's cadet

force, and is divided into six regions, 34 wings and around 1000 squadrons

within communities around the UK.

The RAF

section of the Combined Cadet Force (RAF). Combined Cadet Force welcomes cadets

of all three services coming together in approximately 200 independent and state

schools across the UK.

The cadets

receive flying training thanks to instructors of the RAF Volunteer Reserve

(Training). The flying experience is delivered by the Air Experience Flights

and Volunteer Gliding Squadrons.

12 Air

Experience Flights based mainly on RAF Stations provide air training for the

RAF Section of the Combined Cadet Force.

- No. 5 Air Experience Flight RAF - RAF Wyton (Moving to Wittering in 2014)

- No. 9 Air Experience Flight RAF - RAF Linton-on-Ouse (moved out of Church Fenton in 2013)

The Air

Training Corps gives air experience to cadets mainly through the Volunteer

Gliding Squadrons. Manned by RAF Volunteer Reserve (Training) personnel, the 25

VGSs are based all over the UK and comprise 8 Conventional Glider Squadrons,

equipped with the Viking T1 glider; and 17 squadrons equipped with the Motor

Glider Vigilant T1.

Conventional Glider Squadrons

- 614 VGS (MDPGA Wethersfield),

- 615 VGS (RAF Kenley),

- 621 VGS (Hullavington),

- 622 VGS (Trenchard Lines),

- 626 VGS (Predannack),

- 644 VGS (RAF Syerston),

- 661 VGS (RAF Kirknewton),

- 662 VGS (RM Condor),

Motor Glider Squadrons

- 611 VGS (RAF Honington),

- 612 VGS (Dalton Barracks),

- 613 VGS (RAF Halton),

- 616 VGS (RAF Henlow),

- 618 VGS (RAF Odiham),

- 624 VGS (RMB Chivenor),

- 631 VGS (RAF Woodvale),

- 632 VGS (RAF Ternhill),

- 633 VGS (RAF Cosford)

- 634 VGS (MOD St. Athan),

- 635 VGS (RAF Topcliffe) (Formerly at BAE Samlesbury)

- 636 VGS (Swansea Airport)

- 637 VGS (RAF Little Rissington)

- 642 VGS (RAF Linton-on-Ouse),

- 645 VGS (RAF Topcliffe),

- 663 VGS (RAF Kinloss)

- 664 VGS (Newtownards)

The Volunteer Gliding Squadrons are being equipped with simulators as part of the standing up of the

No 2 FTS. 25 simulators have been ordered and will be distributed one in each

VGS. The RAF hopes to later purchase additional simulators, aiming for a final

fleet of 17 Vigilant T1 simulators and 10 Viking T1 simulators.

No IV Flying Training School – RAF Valley

The School delivers advanced fast

jet training and retains two flying squadrons, 208(R) with the Hawk T1/1A and

the IV(R) Sqn with Hawk T2. As has been explained earlier, the position of 208

Sqn is quite precarious, and the unit doesn’t seem to have a long future ahead.

Advanced Training for Qualified

Flying Instructors (QFIs) is delivered by the school on behalf of Central

Flying School.

IV Squadron is the current core of

the UK Military Flying Training System, and is in the history book as the first

strand of training capability completely delivered via MFTS. The Hawk T2

entered service beginning in 2011 to deliver advanced training at an higher

level than was possible with the T1. The glass-cockpit T2, with its built-in

simulation capabilities, is able to deliver advanced training to such a level

to allow the fast jet OCU squadrons to reduce the length of their courses and

cut the number of flying hours. This saves a lot of money, since Hawk T2 flying

hours are assessed as costing up to 10 times less than Typhoon hours. Every bit

of training that can be downloaded from the OCU to the training squadron, in

other words, means money saved.

The squadron is supported by a

purpose-built training centre, the Moran building, containing the classrooms,

the simulators, the maintenance and administration spaces, and all other

components of the unit’s life. Training on the ground is carried out in four

electronic classrooms (Classroom-Aided Instruction), and on the laptops

assigned to each student, which are fitted with Computer-Based Training

software. All flight manuals are electronic.

Going up in complexity, the training

centre has six Flight Training Devices, which are mini-simulators that can be

linked together and be programmed to simulate the front or rear cockpit

depending on need. The FTDs are simpler than a full simulator, and can be used

by the student on its own, for self-training and rehearsal, while still being

advanced enough to include simulated basic radar use.

There are then two Full Mission

Simulators (FMSs), which are not full-motion, but provide motion-cueing in the

seat. Apart from the lack of full motion, the realism is absolute: the

simulators are treated like real aircraft, and the students only enter them

while wearing full flying gear. The dome-screens can project accurate imagery

reproducing any part of the UK, thanks to a complete mapping database.

The rate of live flying to simulator

in the Squadron is roughly at a 50:50 balance point, overall, with wild

differences in the various phases of the instruction: instrumented flying is

taught up to 80% in the simulator and just 20% in flight, while air combat

training is 90% done in flight.

Flying missions are carefully

planned through Hawk Advanced Mission Planning Aid (HAMPA) with briefings held

in five Virtual Briefing Rooms.

The beneficial effect of simulation

is measured in an improvement in success rates: on the Hawk T1, up to 10% of

the students would fail their course, while less than 0.5% of students fails

the new generation course, a very significant improvement.

A permanent contractor presence is

on the base to ensure continuous availability of the simulators and electronic

systems, and the instructors are all former servicemen chosen among the most

experienced.

The Hawk T2 (Advanced Jet Trainer)

delivers much improved training thanks to its avionics, and in particular

thanks to built-in emulation capabilities. Although the Hawk AJT can be fitted

with external stores and real weapons, training is only done with emulation,

which ensures huge savings. The Hawk T2 has an advanced cockpit with HUD,

moving map display and navigation displayed on three Multi Function Displays

arranged in the same pattern found on Typhoon.

Emulation steps in to give the

student what the Hawk actually does not have: it emulates stores and weapons,

threat warning system and synthetic radar. All of it can be linked in real time

to other Hawks to provide realistic, immersive training.

The trainer in the back seat can

inject simulated threats in the equation in any moment, in order to make things

complex for the student.

The Hawk T2 on delivery was only

programmed to deliver generic MRAAM and IR missile emulation, plus HUD

indications for cannon fire. Basic, generic air to ground weapons were also

emulated. By the end of 2012, however, Ascent has been given clearance to train

the students at SECRET level, with the introduction of specific emulation of

AMRAAM, ASRAAM and Paveway IV employment.

The core training course is

classified RESTRICTED, and continues to use generic weapon simulation, so that

this course can continue to be offered to foreign countries wanting to have

their pilots trained in the UK. IV Squadron will have a small surplus of

capacity due to the cuts the RAF suffered in 2010, and will be able to take on

a number of foreign students even after 208(R) Squadron eventually disbands.

The students don’t use these weapons

for real in the course, but fly their delivery and launch profiles, and get

accurate digital emulation. Thanks to the HUD recorder and to HAMPA, full

debriefings can be carried out after landing, for maximum training effect. By

the end of the training course, pilots fly Multi-Role sorties which include

low-level flight towards a simulated land target to be hit with Paveway IV. On

the way in and out, the student must face simulated threats including enemy

interceptors, which are countered with simulated AMRAAM use. AWACS

communications is also incorporated in these complex training sorties.

|

| The new hangar with the Hawk T2s |

Hawk AJT and related simulation

equipment are also Night Vision Goggles and Air to Air Refuelling capable, so

there is potential for further downloading of training events from the OCU

squadrons to IV Sqn. Considering the savings that this would enable, it is

likely that in the near future this possibility will be exploited.

29 Squadron, OCU for the Typhoon fleet,

expects to be able to shorten its own courses and cut flying hours because of

the higher capabilities students have when they arrive coming from the Hawk T2

courses. Some 65% of OCU training is now delivered via simulation, and the RAF

aims to improve the ration in serving frontline squadrons (25% simulation, 75%

live flying) to aim to the same 50 : 50 ratio promised by the F-35.

In order to achieve this result, the

RAF is planning to buy more Typhoon simulators: currently there are four in

Coningsby (two Full Mission Simulators and two Cockpit Trainers) and two in

Leuchars (will transfer to Lossiemouth along with the aircraft) and the idea is

to purchase a further four (2 for Coningsby, 2 for Lossiemouth) and link them

all together for large virtual training scenarios.

The Typhoon Training Facility in

Coningsby, meanwhile, will be fully staffed by industry personnel by the end of

this year: BAE will hire and supply instructors, chosen from ex-servicemen with

experience. The civilian, ex-military instructors will benefit from greater

stability, and from the lack of additional tasks that they would have if they

were RAF personnel.

Ahead of the withdrawal of the

Tranche 1, which includes a great share of the 2-seater Typhoons, the RAF is

also experimenting whether times are mature for doing away with the 2-seat.

F-22 and F-35 notoriously don’t have a twin-seat trainer variant, and Typhoon

in future might follow, as the trial activity “Pandora’s Buzzard” has demonstrated that pilots can

fly their very first Typhoon sortie solo, without need for an instructor in the

back, even after receiving a 100% simulator OCU course.

Now, such an extreme approach is

unlikely to catch up anytime soon, but much reduced need for 2-seaters and live

flying are pretty much ensured: better training aircraft in earlier phases of

training, and greater use of simulation appear to be the way forwards.

Simulation will also be key in the F-35 training. A OCU squadron for the F-35B force is planned to stand up around 2019 in RAF Marham, and an Integrated Training Centre will be built on the base to house the simulators and training aids. The UK hopes to train foreign F-35 personnel at the centre, and a preliminary agreement is in place with Norway.

A great overview of the Typhoon OCU training is available online here.

Other training and training support squadrons

In here I want to include an

overview of the remaining air training units, which aren’t or are only

partially touched by UK MFTS, and which deliver operational training support.

208 Squadron, RAF Valley: part of No 4 Flying Training School at RAF Valley, 208(R) Squadron flies

the legacy Hawk 1. Initially, it was thought that a short transition course on

the Hawk T1 would be needed for pilots coming from the Tucano, to soften the

move from it to the glass cockpit, advanced Hawk T2 trainer, but it has actually

been proven that such a passage is completely unnecessary, and by the end of

2012, with the Hawk T2 fully established in service, british pilots training

became the task of IV Squadron, with the T2.

208 Squadron was on the edge of

being disbanded, and for all the year its manpower dropped in preparation to

the end of the unit, but it was given a last minute reprieve as part of a

contract signed with Saudi Arabia for the training of RSAF crews, which began

with a first course in February 2013.

208 can so continue to deliver its

services, including some training for Royal Navy pilots destined to tours on

Super Hornet in the US or Rafale in France, and personnel destined to the

Tornado GR4 line. Typhoon students all move through IV Squadron to exploit the

greater capabilities of the Hawk T2.

But for how much longer will 208 be

around? The survival of the squadron goes against the mechanisms of the UK

Military Flying Training System contract, and is justified as “irreducible

spare capacity” in the legacy training fleet. As the MFTS kicks fully into

gear, however, the training fleet will be restructured to much more tightly

conform to the national, british requirement, diminishing significantly the

room available for International Defence Training (IDT). As is noted in the RAF

Airpower 2014/15 yearbook, the incoming reduction in IDT capacity might mean

savings in financial terms for the training fleet, but has negative

consequences on the capability of UK Defence to actively engage with foreign

partners (british flying training being a very successful engine of

international cooperation) at a time in which, formally, “soft power” and

“forward engagement” are the buzzword. Not a very coherent line of action.

Some negative effect could also be

experienced when it comes to military aerospace export, as the offer of british

flying training has, in the past, proven to be an effective tool for making the

british offers more attractive on the market.

The Saudi deal that kept 208 Squadron alive is

temporary in nature: it is an interim solution for the Royal Saudi Air Force,

which needed a gap filler ahead of the standing up of an adequate training

pipeline in Saudi Arabia with the 22 Hawk AJTs that the country purchased. In

2012, ahead of the final agreement, the estimated length for the pilot training

arrangement was 3 years. By 2016, in other words, it might be over. Saudi

Arabia will begin receive its Hawk AJTs in 2015.

100 Squadron, RAF Leeming: flying from RAF Leeming with the Hawk T1/1A, 100 Sqn serves in a mixed

target facilities role (the closest to USAF Aggressor squadrons the RAF gets),

supports exercise and training activities and provides dedicated aircraft in

support of the Joint Forward Air Controllers

Training and Standards Unit, which is also based in Leeming and is

the only NATO and US Joint Services accredited schoolhouse in UK Defence to

train Joint Forward Air Controllers.

The question for the

future of this squadron is the same question facing the Red Arrows and 736 NAS:

what after Hawk 1? For now, it seems that the OSD of the Hawk 1 has been moved

to the right again, out to 2020, in order to gain time for a decision on the

way forwards. A further purchase of Hawk T2 might or might not be the solution

to the problem.

736 NAS, RNAS Culdrose

and RNAS Yeovilton: recommissioned on 6 June 2013 and first deployed to RAF

Lossiemouth for exercise Joint Warrior in October the same year, the squadron

is a maritime aggressor unit equipped with 14 Hawk T1. The Squadron is based in

Culdrose, with a detachment in Yeovilton. 736 NAS was formed from an

amalgamation of the Yeovilton Hawkdet (formerly Naval Flying Standards Flight

(FW)) and the Fleet Requirements and Air Direction Unit, a unit of civilian contracted

pilots provided by Serco Defence and Aerospace which flew Hawks in simulated

air and missile attacks against Royal Navy ships in pre-deployment training.

The Hawkdet remains as a 736 Detachment in Yeovilton, and the tasks of

the FRADU have been all taken over by the new, uniformed squadron. The Hawks simulate enemy fighter aircraft attacking the ships, or high-speed

sea-skimming missiles which are fired against ships to allow the crew to train

in the procedures to avoid and reduce the damage caused.

The pilots also fly missions for the students of the Royal Navy School

of Fighter Control. Fighter Controllers are responsible for controlling and

guiding the friendly fighter assets assigned to a group of ships.

In a similar role, the aircraft are also tasked to support the training

of RN Observers in the Airborne Early Warning role for 849, 854, and 857 NASs.

These missions involve airborne fighter control, as well as the identification

of ground targets.

736 NAS hopes to in future serve as an Aggressor squadron in support of

training, particularly for the F-35B when it comes. Again in support of the

F-35B force build-up, 736 NAS will provide an invaluable holding unit where

pilots coming back from exchange in the US or France on F-18s and Rafales can

continue to fly and stay up to date, while also refreshing UK maritime methods

ahead of the passage into Joint Lightning Force.

115(R) Squadron, RAF

Cranwell: 115(R) is tasked by the Central Flying

School with the conduction of the flying stage of the training course for new

Qualified Flying Instructors (QFIs). The squadron runs two courses, Main and

Refresher, which are meant respectively to prepare new instructors the first,

and to re-qualify instructors which are switching aircraft type or have been

away from teaching for too long. The squadron basically trains the trainers

that will then serve in Elementary Flying Training squadrons (16(R), 57(R), 703

NAS, 674 AAC). The squadrons does this on behalf of the Central Flying School

in RAF Cranwell, which is the RAF’s primary institution for the training of

military flying instructors, for testing individual aircrew, audit the Flying

Training System, give advice on flying training and provide the RAF Aerobatic

Team. Established at Upavon on 12 May 1912, the Central Flying School (CFS) is

the longest serving flying school in the world.

115(R) Squadron employs the Grob G115 Tutor T1. The squadron is

transferring this year from

Cranwell to RAF Wittering.

Joint Services Air

Tasking Organisation JSATO: JSATO is a small

organization with HQ in Yeovilton which tasks the aircraft and systems employed

in support of air training. They are in particular associated with the fleet of

14 Dassault Falcon DA-20 provided under contract by Cobham Aviation Services to

support advanced training exercises.

6 DA-20 are based in Durham Tees Valley International Airport, and have

the primary mission of supporting RAF exercises. A second flight of 6 DA-20

flies from Bournemouth, primarily tasked with Royal Navy training. A further 2

aircraft are held in reserve as part of the contract, and resources from the

two flights can be mixed to provide service to RAF or RN in any moment.

The DA-20 modified for JSATO service is a crucial element in combat

training as it delivers Electronic Warfare and radar jamming to complicate the

work of fighter jet pilots, AWACS operators and radar crew on ships and

helicopter AEW of the Navy.

The aircraft is fitted with a powerful ESM suite located in a fairing

under the fuselage, and can carry up to 4 pods under the wings which give it a

series of capabilities, including that of electronically impersonating fighter

jets (such as Su-27 and Su-30, for example) with their sensors and armament.

To do that, the DA-20 carries an Air Threat Radar Simulator; an I/J band

jammer to disturb interception radars; an E band Jammer to disturb AWACS and a

Rangeless Airbone Instrumented Debriefing System (RAIDS) to interact with other

aircrafts in training and deliver accurate, detailed mission debrief after

landing.

The aircraft also has an ALE-40 chaff dispenser so it can defend itself

like a real combat aircraft, adding further realism.

A part of the aircraft are fitted with Real Time Monitoring System,

which takes information via the RAIDS network and allows the crew to serve as

Range Training Officer, monitoring the exercise as it happens.

The DA-20 has a crew of 3: a captain, a first officer and an EW Operator.

Usually, Cobham hires ex-servicemen to serve in these roles in the JSATO fleet.

The DA-20 puts ships and aircraft, including Sentry E-3D and Royal Navy

Sea King ASaC helicopters, in the condition to train realistically and face the

disruption of electronic warfare and jamming, while extensively simulating the

radar and armament capability of enemy attack aircraft. The DA-20 of course is

not a fighter jet, but it brings the electronics to bear, supporting the

Aggressor squadrons (100 RAF and 736 NAS) who deliver the kinetic part of the training

with the Hawk.

The Hawks do the maneuvering, and the DA-20 cloaks them indirectly to

turn them into missiles and enemy fighters. The combination is pretty potent,

and comes at an affordable price.

Under the contract, Cobham is to provide 3500 hours of flight in support

of RN training, 2500 hours in support of the RAF and 500 contingency hours each

year.

.jpg)

Gaby

ReplyDeleteSurely they can't close Midldle Wallop! It's the unofficial spiritual home of the Army Air Corps. Their museum is there and there are all the emotional asociations with the WWII fighter station. Still, I don't suppose sentiment counts for much in the present ruthless age.

I have left another post for you under the heading FCAS, if you can spare the time to answer.

Weird, i replied to this post the other day, but now i can't seem my post. Blogger must have screwed up again.

DeleteAs i said earlier, the Army will definitely be trying to resist the call for closing Middle Wallop, but there are some questions to be answered regarding its future use, as i explain in the article. It looks pretty likely that, asked for sacrifices, the army might have to move away to avoid worse losses elsewhere.

That will have to be seen, though.

Excellent post Gaby, a real wealth of information, thank you!

ReplyDeleteCorrect me if i'm wrong but RAF Linton-on-Ouse, Scampton and Leeming all seem to be quite sparsely populated for fully operating bases (as apposed to St Mawgan, Wittering and many others that have ceased flying operations and now only host ground units).

If 72 squadron moves to RAF Valley as you predict then do you think we will see a much overdue rationalization of these 3 sites into 2 or even 1 instead?

Although it is not clearly said, i read the move of flying training to Valley as the signal that Linton will be closed, so there will certainly be a fair amount of change.

DeleteWhat about Scampton? Wasn't their a plan a while back to move the Red Arrows to Leeming and thus close the base? Or was that pre SDSR and long since scrapped?

DeleteIt was announced in 2012 that the plan would not go ahead. The idea had been to transfer the Red Arrows in Waddington during 2014, but it was assessed that their impact on the use of air space would be negative. Besides, closing Scampton hinged on being able to move the Air Surveillance and Control System (No 1 Air Control Centre) to another base, and it was concluded that this would be too complex and expensive.

DeleteThe idea was scrapped, and the runway resurfaced and renewed later in 2012, with the Reds temporarily moving into Cranwell.

Gaby

ReplyDeleteThanks very much for the reply.

Hello Gabby, very informative as ever, a different subject to training but will the current situation in Ukraine / Russia have any effect on on the NATO SALIS agreement?, many thanks.

ReplyDeleteNo suggestion so far about trouble coming up on that front, at least that i know of.

DeleteGaby

ReplyDeleteI am slightly concerned by the fact that the Lynx AH9 is scheduled for retirement by 2018. I feel that the Army will be left without, for want a of a better term, a utility helicopter. I do not consider the Wildcat to be a genuine utility aircraft, it being more suited to reconnaissance etc.

Extending the Lynx A9's service for a few years would give the Army chance to have a look at a few possible successors. Perhaps you disagree?

The 9A hasn't much more than Wildcat to offer in Light Utility role, but its loss will mean a gap, yes. At the very least, one squadron's worth of light assault helicopters is required for SF support, and the uncertain status of the announced Wildcat LAH variant, which did not go ahead for now, leaves a question mark on future plans.

DeleteA further extension of 9A is a possibility, but in the early 2020s the problem of absorbing the loss of Puma and 9A will again be at the top of the page.

Ideally we would see more Wildcats procured to replace the 9A, even if not on a 1-1 basis, not holding my breath though!

DeleteWhat about Puma? It seems pretty unquestionable that they will be scrapped by 2025 at the latest (despite a £500+ million upgrade!) and the SDSR called for only 4 main helicopter types in the future. However, overall numbers aside i've heard Puma provides a medium lift insertion capability that Chinook is too big and Wildcat too small to deliver.

Do you think their is much hope of a dedicated replacement?

As of now? Honestly, no. JHC seems to expect no replacement either, and they are making long term plans on numbers which suggest Puma goes and nothing comes in. But Puma does indeed deliver a capability in an interesting, middle range, carrying a decent number of troops and equipment while being small enough to fit into cramped landing zones and to fit inside a C-17 with relatively minimum dismantling: Merlin takes ages to be ready after being air-lifted to distant theatres, and so does Chinook. Puma can be ready in four hours after the C-17 lands.

DeleteMerlin and Chinook can self-deploy, to a degree (Merlin did fly on its own to Iraq, for example), but Puma offers some things that they can't give.

Never really liked the Puma to be honest, seen one too many bad reports from ex pilots saying it's a bit a pig to fly!

DeleteHowever their will clearly be a medium sized troop carrier gap once Puma goes, what with Merlin already in the stages of being handed over to the RN as well.

In my view the lost opportunity was when it came to replacing Lynx. Whilst Wildcat looks like it will turn out to be a decent recce and light utility helicopter it's troop carrying capacity of 7 (including a door gunner) is VERY light indeed.

The AAC should have instead pursued a mid sized helo that was big enough to carry a dozen plus troops for insertion work in difficult locations and special forces ops but could also perform all of the general 'utility' and recce stuff the Lynx/Wildcat does at the same time.

Everyone always seems to advocate the American Blackhawk when this question comes up, but it seems to me the AW149 would have provided for the needs of the service whilst also satisfying the inevitable political dimension by still providing work for Augusta-Westland.

Gaby

ReplyDeleteMany thanks for your reply. I think I might have put my question on the wrong thread, though. Thanks anyway.

No real worries about that. I don't receive that many comments, so it is not a problem.

Delete