What is the current status of the

F35 program, and what the timeline for production and release to service of

this or that capability? It is not easy to answer, among the chaos created by

press articles which are normally either full or hype or full of gloom.

This adds confusion to a program

which is already very complex in itself: it’s very easy to get lost among

LRIPs, Blocks and test points.

In this article I’ve tried to put

together an overview as clear as possible, also creating a graph which should

help making things much easier to understand.

During the year 2012, the F35 fleet

exceeded the year targets in terms of flights and test points cleared: the plan

called for 988 flights and 8458 Test Points, but by December 2012 the fleet had

achieved 1156 Flights and 9282 Test Points. All three variants (A, B, C) exceeded their

in-year targets, according to Lochkeed Martin.

The Director, Operational Test and Evaluation

(DOT&E) report for 2012, which was mentioned in countless press reports, says differently

because it is valid only out to November 2012. By then, F35B and C had already

exceeded their test flight targets, while the F35A had flown 263 times against

a plan for 279.

The Test Flights are a much more

complex subject. The DOT&E, again, valid and up-to-date up to November

2012, says that 8750 test points were achieved, against a planned 6497 TPs.

However, the 8750 points have been obtained by anticipating 2319 points that

had been planned for future years, in exchange for 1786 points which, planned

for 2012, had to be postponed as issues were discovered on the airplanes, that

prevented relevant testing from happening. The discovery of these issues has

also caused the emergence of 1720 further Test Points that had to be

achieved.

The F35 (all variants), achieved

4711 of the 6497 TPs planned for 2012, but also cleared 1720 additional test

points that emerged due to corrections to the aircrafts and 2319 test points

originally planned for the next years.

In terms of software, validation of

the Block 1 package exceeded its targets by 35%, but Block 2 lagged by 6% and

Block 3 is also lagging and “made virtually no progress” according to the

DOT&E. This could prove a big issue, since Block 3I is planned to begin

flight testing later this year.

The DOE&T provides a clear

explanation of the nature of the 3 Blocks of software (which actually break

down into several sub-blocks):

Block 1. The program designated Block 1 for initial training capability and allocated two increments:Block 1A for Lot 2 (12 aircraft) and Block 1B for Lot 3 aircraft (17 aircraft). No combat capability is available in either Block 1 increment. (Note: Remaining development and testing of Block 0.5 initial infrastructure was absorbed into Block 1 during the program restructuring in 2011.)

Block 2. The Block 2 software was broken down

in two releases:

Block 2A. The program designated Block 2A for advanced training capability and associated this block with Lots 4 and 5. No combat capability is available in Block 2A.Block 2B. The program designated Block 2B for initial, limited combat capability for selected internal weapons (AIM-120C, GBU-32/31, and GBU-12). This block is not associated with the delivery of any production aircraft. Block 2B software will be used to retrofit earlier production aircraft.

The Pentagon

has already started the process for the upgrade that would retrofit the early

deliver airplanes.

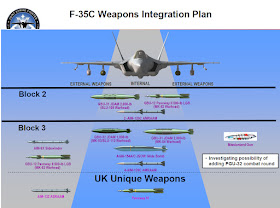

Block 3. The Block 3 is fundamental as it represents the first “mature” standard

for the F35. For the UK it is even more important, because british weapons will

only be integrated as part of the Block 3.

Block 3i. Block 3i is Block 2A capability re-hosted on an improved integrated core processor for Lots 6 through 8.Block 3F. The program designated Block 3F as the full SDD capability for production Lot 9 and later.

The release to

service of the software blocks remain one of the most challenging aspects of

the F35 program, and delays have so far been a constant. The first two british

F35B (BK-1 and BK-2), part of the LRIP lot 3, were planned to have Block 1B

capability, but were delivered, along with other US F35s, with only partial 1B software.

The third F35B

for the UK should be delivered later this year and being part of the LRIP 4 it

should come with Block 2A software, but will almost certainly have only partial

capability, as LRIP 4 deliveries started in November 2012 but the software

still was incomplete.

In time, this

software issue will be corrected, but of course it represents an issue, because

the final development of the 2A software will have to happen concurrently with

the testing and development of the 2B software.

It is not yet

clear when the 2B software will appear onto the airplanes, as it is not

associated to a specific production lot, but will be uploaded into the

airplanes when available. The plan is to achieve full 2B capability release to

service by early 2015, however.

Inserting Block

3 software onto the early production airframes will be more challenging, as it

will also require an hardware upgrade, with new processors replacing the

current ones. Software Block 3I is planned to begin flight around the middle of

2013, while 3F will begin its own 33-months testing and development phase in

early 2015, with the aim of release to service in 2017.

The software

delays and challenging, concurrent development and testing comes in addition to

a series of other problems that have to be solved, including the helmet mounted

display, particularly in its night-vision function, the F35B propulsion system

and, perhaps the most worrisome, the cracking of airframe bulkheads and

elements well before the 8000 flying hours value the F35 is supposed to reach.

While the

helmet fixes, the software, the processors and other issues are (relatively)

easy to retrofit and correct, getting the airframe right as soon as possible is

key to avoid procuring expensive aircrafts that end up having limited use and

short life.

Going back to

factory to implement changes and fixes has a cost: the 3 F35s ordered so far

have already incurred a cost growth of 26 million pounds due to corrections and

design changes, the NAO 2012 report warns.

I will not

write about the issues remaining to be solved in this article: reading the

DOE&T report gives a clear picture of the state of things. I want to focus

instead on the british F35 force, and see what challenges and milestones lay

ahead on the path for its generation.

Two of the next

big events in the british F35 saga are the delivery of the third F35B, BK-3

(ZM138) and the confirmation of the order for a fourth aircraft, which will be

part of the LRIP 7. Both milestones should be hit in the next months.

BK-3 is a jet

of the Low Rate Initial Production (LRIP) 4, so it is more advanced and mature

than the previous two, but as we already said it will have no combat capability

and incomplete 2A software. After delivery, it will move to Edwards Air Force

Base, home of the F35 Integrated Test Force, composed by 461 Test and

Evaluation Squadron, 412 Test Wing.

The 461 Sqn

flies the test sorties to validate the Test Points of the F35 program, but in

2012 it has also delivered training to the personnel from 31 TES squadron

(USAF) and VMX-22 (USMC), which are among the squadrons which will

Operationally Evaluate the F35 system.

The System

Development and Demonstration (SDD) fleet is split between Edwards AFB and NAS Patuxent

River: according to Lochkeed, as of January 2013, Edwards AFB has 6 F35A of the

SDD production lot and “2 LRIP jets devoted to SDD” which I think are the

british BK-1 and BK-2.

It

was BK-1 which aborted a take off at Edwards on January 16, 2013, because

of a fueldraulic failure, which caused the precautionary grouding of all F35Bs

to be ordered on January 18.

The NAS

Patuxent River instead has 7 F35B and 4 F35C of the SDD production lot and 2

LRIP jets devoted to SDD.

The first two british

F35Bs will be jointed at Edwards by BK-3 later this year. They have been used

in support of testing and training, but in good time all three will join the Operational

Test and Evaluation (OT&E) fleet.

In an official document dating back to 2009, the Edwards-based OT&E force

at full capacity was expected to contain 6 F35A of the USAF, 6 F35B of the US

Marines, 6 F35C of the US Navy and 2 british F35B. Since then, some things have

changed, along with the relevant dates, that have slipped further to the right:

a third british F35 was added, being ordered in 2010.

Just today, Flightglobal

reports that the USAF F35A OT&E force is about to get its first

aircrafts: the OT&E force is the 53rd Test and Evaluation Group,

Nellis AFB. It controls two squadrons: 31 Test and Evaluation Squadron at

Edwards AFB and the 422 TES at Nellis. Over the last week of the month, the 31

squadron will receive four F35A Block 1B, while the 422 will get an equal

number of Block 2A.

The F35B

OT&E should stand up at Edwards in mid-2014, US Marines said in March 2012. The detachment will

have the colors of VMX-22, the same squadron that evaluated the MV-22 Osprey

tiltrotor. The three British F35Bs will work in close partnership with them, I

understand, but for now they remain formally part of the training squadron

VMFAT-501 “Warlords”, serving to augment the number of airplanes available for

the training of pilots. BK-2 briefly visited Eglin air force base before moving

to Edwards.

Eglin is the

location of the F35 Integrated Training Center, a tri-service and international

school for pilots and ground crew which will offer ten Full Mission Simulators,

1 Ejection Seat Trainer, 5 Weapons Load Trainers, classrooms and other

supports.

The ITC is of

course completed by flying training squadrons: for the US Marines, this is the

already mentioned VMFAT-501 “Warlords” squadron, which is planned to eventually

line 20 F35B. To these, the United Kingdom will add 6 F35Bs of its own.

The US Navy will

have the VFA-101 “Grim Reapers” squadron with 15 F35C, and the USAF will have

the 58th Squadron “Gorillas”. I had already written a good overview

of the Eglin ITC and its components, here, which I recommend reading.

The fourth F35B

to be ordered by the UK, part as we said of the LRIP 7, should be delivered

sometime in 2015, and it is the first aircraft for the training fleet, so, if

the plans do not change, it will be based at Eglin with the Warlords, while

BK-1, BK-2 and BK-3 could very well stay in Edwards in the Operational

Evaluation role out to 2017/18.

Five more

aircrafts will have to be ordered soon to complete the envisaged six-strong

british OCU at Eglin. It appears to me necessary, to meet the officially

announced targets in the dates indicated, to order several F35 next year, that

would thus be part of LRIP 8 and due for delivery in 2016. The order should

include enough airframes to at least complete the training fleet at Eglin, I

suggest. Without it, it’s hard to imagine how the UK could be ready for the

beginning of land trials in the UK in 2017 and for the first trials on HMS

Queen Elizabeth in 2018.

In addition, Minister

Philip Dunne, speaking about the switch back to the F35B, declared that the

first F35 would arrive (in the UK, I’m guessing) in 2016, so an order for at

least six aircrafts would be needed, assuming that priority is given to putting

together the training fleet before flying the first jets to the UK.

It will also be

necessary to finally, officially select the Main Operating Base for the F35 in

the UK, with Marham having the status of favorite. The official announcement

might be part of the basing review to be announced sometime this year.

A total of 48

F35Bs has been funded and planned as part of the 10-year budget, out to

2022/23. Of these, if the plans do not change, 3 are OT&E airframes and 6

will form the training fleet at Eglin. This leaves a maximum of 39 airframes to

use to form frontline squadrons. With a strength of 12 airframes each, the

squadrons that can be formed with 39 aircrafts are, most likely, only two,

unless the MOD shows more “audacity” that it is usual and forms 3 squadrons,

accepting the risk of having a tiny Sustainment Fleet thanks to the assumption

that more aircrafts will be ordered later, and thanks to the awareness that the

production line for the F35 is due to stay open and hot for many, many years.

The Permanent Under Secretary for the MOD, Jon

Thompson, said to the

Defence Committee:

The Joint Strike Fighter has a very

long tail. It is more than 10 years. Our commitment over the first 10 years is

for 48, which was part of the announcements on 10 May in relation to the

reversion to STOVL. Over time, we would expect the number to rise to beyond

three figures, but that would be in the second decade.

With additional

orders to follow, giving priority to achieving a 3 squadron frontline force

wouldn’t be absurd. It would also allow government to make it more credible

their claim that, when needed, it is still possible to deploy an aircraft

carrier filled with a full 3-squadron, 36 jets air wing.

The manning of

the Joint F35 force is officially going to be a 60:40 affair in favor of the

RAF, and it isn’t clear how this will affect squadron colors. I hope and expect

that one of the squadrons will bear Naval Air Service colors.

The stated

targets for the F35 build-up are:

Land-based IOC

to be achieved in March 2019

Carrier-based

IOC to be achieved in March 2021

The business plan 2011, while speaking of the F35C and not

of the B, is interesting as it provides an indication of the date of

“end-activity” for the first phase of procurement and build-up of the F35 force

as April 2023.

The business plan 2012, accounting for the return to F35B,

maintained the April 2023 end-of-activity date, and detailed the IOC dates. It

has also been publicly announced again and again that trials aboard HMS Queen

Elizabeth will begin in 2018.

By April 2023,

in other words, the full force of 48 F35B aircrafts announced as funded within

the 10-year budget will have to be operational. And to achieve the IOC dates as

currently announced, sizeable orders of F35 jets are to be expected in the next

few years. The problem is, of course, the maturity of the airplane and,

crucially, of its software.

While the US

Marines plan to hit initial operating capability around 2015/16, with the

software 2B, the UK will have to wait until Block 3 to have its own weaponry

integrated. The latest publicly available official document treating this subject dates back to March 2012: it shows that the sole F35B, to enable the US Marines

to hit IOC, will be cleared in Block 2 to carry and employ weaponry, although

consideration is being given to integrating weapons early on all variants to

reduce risks.

Block 2 F35B is

contracted to be able to employ the following arsenal:

Internal carriage on F35B Block 2

2x 1000 lbs

JDAM GBU-32

Or

2x GBU-12

Paveway II

And

2x AIM-120C

AMRAAM

External carriage on F35B Block 2

None

With the

software Block 3, the F35B would see its arsenal expanded to include:

Carriage of 4

internal AMRAAM missiles (2 additional missiles in place of air-to-ground

weapons)

External

carriage of GBU-12 Paveway II

External

carriage of 2 AIM-9X Sidewinder

Gun pod

Consideration

was at the time being given to the possibility of integrating within Block 3

the capability to employ PGU-32 SAPHEI-T (Semi-Armor Piercing

High Explosive Incendiary-Trace) rounds for the 25mm gun. The US are

also thinking about adopting the Frangible Armor Piercing (FAP) round made by Rheinmetall Waffe

Munitions Schweiz.

Block 3 would then add the possibility to carry 4 internal AMRAAMs (two on the internal Air-Ground stations), in addition to the integration of further US weaponry.

The March 2012 report

still assumed the UK would buy F35C, so it is on the C Block 3 page that ASRAAM

and Paveway IV appear: Paveway IV is only cleared for internal carriage (this

seems to have always been the plan, even if I cannot possibly agree with it and

would really, really encourage external integration too) while ASRAAM is

cleared only for external carriage.

This second

element was a surprise.

Originally, the

UK had asked to integrate, in Block 3, the ASRAAM for quadruple internal

carriage. Weird choice if there ever was one, as I can’t understand what was

the intended role of a modern day Sea Harrier FRS1 armed with sole short-range,

infrared guided missiles.

Perhaps common

sense won the day at some point, or maybe it was just budget cuts biting, or

the difficulties in adapting a rail-launched weapon to pylons meant to drop

air-ground ordnance, but with Planning Round 2006, the MOD dropped the

requirement for the 2 internal ASRAAM missiles to be carried on air-ground

stations, replacing it with a much more realistic requirement for carriage on

the wingtip rails.

This change of

plan was reported by Jane’s in 2008, but the NAO Major Project report shows it

as a Planning Round 2006 decision. In the same period, the MOD decided to drop

the requirement for external integration of Paveway II and III bombs and

dropped the plan for integration of Brimstone for internal carriage. External

carriage was planned, along with Storm Shadow integration, obviously external,

for the Block IV software release, but even this plan was cancelled, leaving

only ASRAAM and Paveway IV currently contracted for integration.

Since 2008, the

plan has been for integration of 2 internal and 2 external ASRAAMs: two on the

weapon bays’ doors, and two under the wings.

So, the March

2012 graph showing integration only on the external pylons was a nasty

surprise.

At the time of

the switch back from C to B there were confused reports, on the Telegraph and

elsewhere, about the reported impossibility to have ASRAAM integrated in Block

3 on the F35C. They didn’t sound right at the time, but some journalist might

have heard something about difficulties in integrating ASRAAM on the two bay

door stations.

|

| An early mock-up showing ASRAAM installed at the weapon bay's door station, showing a notional swing-out rail. It is currently not clear if the effort to make this happen for real is going ahead. |

At the moment,

I have no idea if the switch back to F35B can solve this issue and give the UK

the intended 2+2 integration model. As I had already reported in an older

article, integration of the ASRAAM for internal carriage, even on the bay door

stations, is far from straightforward:

The ASRAAM is a rail-launched missile, which fires its engine and shots forwards off the rail, like Sidewinder. Meteor and AMRAAM can be rail launched, but can also be dropped like bombs, with the engine igniting after launch. This feature is indispensable for launch of AMRAAM and Meteor from the 4 underfuselage weapon stations of the Typhoon, and from those of the earlier Tornado F3. It is a feature essential to use of the AMRAAM from the F22's weapon bays. And it is essential for the use of the missile on the F35. Integrating AMRAAM and Meteor on the Air to Ground hardpoint is easy because the missile can be dropped out of the bay. ASRAAM cannot be dropped, so it needs the trapeze swinging out.Problem is that the Air to Air station inside the weapon bay's door is also an ejector, not a rail. No problem for dropping a Meteor or AMRAAM, but no rail-launched weapon: the very reason why the US are not bothering trying to integrate Sidewinder for internal carriage.The RAF instead is. While they are not funding Meteor integration, which would be more straightforward and far more useful, they are wasting money in finding a way to fire an ASRAAM from a non adequate hardpoint. I've no details on the solution chosen, but we can exclude that the missile is being modified to be droppable, otherwise the requirement for 4 internal missiles would still be standing. Besides, the NAO report specifically says that existing ASRAAM missiles are to be used for integration work and trials, so the modification is airplane-based, not missile-based.So, while this is speculation, i believe it is 99% safe to assume that, thanks to the small diameter and tiny fins of the ASRAAM making it possible, some kind of swing-down rail is being designed, specifically for use with ASRAAM on the bay door hardpoint.As a standard, the F35 internal hardpoints come with pneumatic ejectors that literally "push" down the ordnance: dropping it and letting gravity do the job won't work as it would never give the bomb or missile the velocity required to pierce the boundary layer and get out of the bay without hitting anything.We are talking about a 40G accelleration, so it is not at all a mean feat as it would at first seem.Most ejectors in service today are pyrotechnic, but the F35 uses safer pneumatic systems. The company building the F35 pneumatic ejectors, EDO, already produces the LAU-142 AVEL vertical ejector for the F22 Raptor's weapon bays. For the F35, they are developing the nuLAU-120 (Internal) and nuBRU-30 (external) systems. An old, but interesting overview of EDO's works and components for the F35 is available here.

Having ASRAAM

integrated for internal carriage is also challenging due to the environment of

the weapons bay, which is quite a hostile one, it has emerged. Temperatures

within the bays get quite high, and this is unlikely to be good for an imaging

infrared guided missile.

I wouldn’t be

excessively surprised to hear that integration of ASRAAM for internal carriage

has turned out to be too complex and expensive to be attractive. It would be a

shame, but in itself it wouldn’t be too big of a problem. The issue is that the

UK still hasn’t given the go ahead for Meteor integration on F35, and it plans

to retire AMRAAM sometime in 2017. Actually, the plan was to retire it in 2015,

but the delays incurred by Meteor integration on Typhoon and release to service

will force the MOD to keep the AMRAAM stocks “alive” for at least a couple

years more. And this implies costs and, more worrisome still, technical risks,

as the missiles have a finite shelf life that is approaching its end.

If a couple of

internal ASRAAM in place of AMRAAMS was admittedly bad, no internal air to air

missile is obviously even worse.

| |

| 2011 payload info |

There might

still be hopes to have Meteor relatively soon on the F35, however. During the

course of 2012, several reports came out about early work ongoing to prepare

Meteor for use on the JSF. In

particular, in July 2012, AIN online reported:

MBDA has just finished work on a preliminary contract with Lockheed Martin to study how Meteor will fit into the F-35’s internal weapons bay. Wind tunnel tests to study the airflow around the bay doors as the missile is ejected will be next. The UK’s first operational F-35s will carry AMRAAMs, but the Meteor is scheduled for the stealth fighter’s Block 4 software release.

The

already quoted March 2012 document provided a list of weapons candidate for

integration as part of the Block IV software work, but Meteor wasn’t present. It

could have been added between March and July. In Italy, roughly in the same

period, there were a few quiet rumors of possible collaboration between UK and

Italy for putting out, finally, the requirement for Meteor integration.

In

early 2012, finally, a US officer involved in the F35 program had said that a

final decision on what will be part of the Block IV software release will only be made by March 2013.

There

is still hope: we might soon enough hear the announcement that Meteor

integration has been added to the Block IV software development program. I

really hope we do, because Block IV won’t enter service with full capability before

2020, so that there is already going to be a gap of several years, unless the RAF’s

AMRAAM stocks get life-extended. Trials of Block IV are expected to begin at

some point in 2017, but delays with software are common, as we already saw.

Block

IV weapons so far include the Small Diameter Bomb II, with IOC planned in 2020,

JSOW C-1

and

the Norwegian Joint Strike Missile. The Turkish stand-off missile is a

candidate, as are the AIM9X Block II and the laser-JDAM.

A

variety of rounds for the 25mm gun and other guided bombs, including Paveway

III, could also made it into the list. And a little publicized candidate, for

the American F35A only, is the B-61 nuclear bomb, which was a design-driver for the

size of the weapon bays.

Block IV should also include integration of the specially designed 426 gallon transonic external fuel tanks. If this goes ahead, it will be interesting to see if the UK orders them.

Block IV should also include integration of the specially designed 426 gallon transonic external fuel tanks. If this goes ahead, it will be interesting to see if the UK orders them.

|

| The above images, from www.f-16.net, show the particular shape of the F35-optimised external fuel tanks. |

The

UK plans to integrate SPEAR

Capability 3 on the F35 for internal (and external?) carriage, and Storm

Shadow is also planned. Brimstone 2 or a further evolution of it (under SPEAR

Capability 2) is in my opinion also likely to re-emerge as a requirement as

well, but perhaps for sole external carriage, as a close air support weapon,

since SPEAR 3 is a much more “strategic” stand-off weapon which would be overkill for most

battlefield engagements. SPEAR 3 is expected to be perfectly capable to destroy

a moving tank, for example, but most of the time this task does not require an

advanced, expensive stand-off (more than 100 Km range) missile, after all.

We also do not yet have a clear idea of what the UK will do about the gun system. I personally expect that at least a number of gunpods will be purchased, but the MOD can come up with the weirdest ideas, as we know well.

Chief

of Defence Materiel Bernard Gray recently told the defence Committee that “our

ability to fit UK requirements into the Block 5 upgrades has been maintained,

so our position in the [F35] programme is unaffected.” This suggests that, with

(hopefully) the exception of the Meteor, SPEAR 3, Storm Shadow and other UK

eventual requirements will have to wait for the Block V software and hardware

upgrade, which most likely means pushing back their entry into service to well

into the 2020s.

The LRIP 6 is expected to contain 31 US and 5 International F35 aircrafts:

18 F35A for the USAF

6 F35B for the USMC

7 F35C for the US Navy

3 F35A for Italy

2 F35A for Australia

Australia will take the first two F35A to base them in the US for training purposes, but it announced a delay of two years to the order for its first 12 production aircrafts.

The LRIP 7, as of January 2013, is expected to include:

19 F35A for the USAF

6 F35B for the USMC

4 F35C for the US Navy

3 F35A for Italy

1 F35B for the UK

2 F35A for Norway

2 F35A for Turkey

The turkish order is however now on hold, and risks to be postponed. Japan instead should receive the first four F35A in LRIP 8.

The

F35 is progressing, things are moving, but much remains to be done. The

building up of F35 combat capability, for a number of reasons, seems destined

to be quite slow. As a consequence, considering that the Tornado GR4 out of

service date has now been set for March 2019, the build-up of the Typhoon force

and of the Typhoon’s capability is particularly important. In a future article I

will provide an overview of the Typhoon situation.